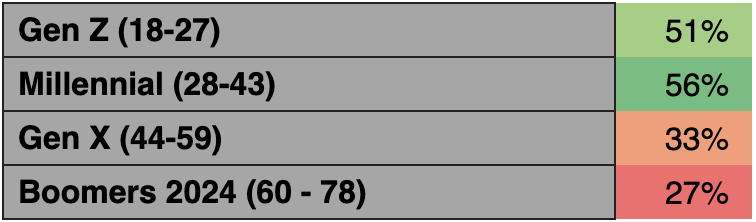

“Declining nightclub trends”; “End of hedonism?”; “Young people are being priced out of nightlife”: these are amongst the latest gloom-monger headlines bemoaning youth in some parts of the world for not being spotted outside-outside. The international headlines – from South Korea, to Berlin, Brooklyn, and the UK – insist the kids are not guzzling enough Jäegerbombs or tequila shots to induce drunken stupors while simultaneously sustaining nightlife economies. They are not in the clubs as much anymore! South African youth, on the other hand, cannot relate. Bars and social drinking culture outside-outside are faring relatively well compared to the alarm bells ringing for youth in other parts of the world. A report published last year by CGA by NIQ (a market measurement consumer intelligence firm for the food and drink industries) confirms that South Africa’s young people’s visitation rates are up when it comes to going out for entertainment, including drinks, food, and experience-led venues. They are the most lucrative market. South Africa’s Gen Z are at 51%, visiting licensed venues on a weekly basis. These figures go up for Millennials (with a higher proportion of employed consumers), with a striking 56% of weekly visitors. As consumers get older, these rates drop significantly (33% for Gen X, and 27% for Boomers). Surprisingly, despite South Africa’s crippling youth unemployment, exacerbated by the country’s stagnant economy, we are outside: bana ba straata – the youth of the streets.

Beyond the nightlife economy and ecology of young South Africans being outside in the streets, the partying and groove cultures embedded therein carry with them sociolinguistic and political registers. What does not in post-apartheid South Africa?

––– –––

‘Straata’ as a recent cultural phenomenon was arguably popularised by Amapiano superstar, Focalistic. He has dubbed himself ‘President ya Straata’, eponymously becoming the name of his EP in 2021. The same year, he was nominated for Best African Act at the MTV Europe Music Awards and was announced as one of the brand ambassadors of the global alcohol brand, Jägermeister. The cover of his EP is an on-the-nose political allusion – an editorially photographed presidential portrait of himself. His dark skin tone flawlessly airbrushed. He wears Louis Vuitton designer sunglasses and ring-sized hoop earrings that attempt to cosplay as demure, but the camera reveals them to be a front: the diamonds are retouched to a subtle, not-so-subtle glisten. South Africa’s seat of government, the Union Buildings in Pretoria, is photoshopped into the background. His outfit also stresses accessible visual cues that communicate authority and power: nebulous military garb complete with epaulettes; a ‘House of Representatives’ coat of arms; and a green sash and badges synonymous with military hierarchies.

Symbolically, it is a militarised self-appointment: the Streets need a leader, and he accepts. Focalistic unanimously positions himself as a contemporary tastemaker, especially with the influence of his viral, popular earworms amassing thousands and then millions of views on social media platforms like TikTok and Instagram. Additionally, his self-appointment raises affirming eyebrows if you are impressed by credentials. Focalistic graduated with a Political Science degree from the University of Pretoria, and his late father was a political journalist for the national broadcaster. As far as his leadership performance review goes, the vitality of youth hedonism in South Africa is certainly in full swing. He is doing a good job – he delights and encourages partying culture’s sustained youthful moxie. The lead single from the EP, 16 Days No Sleep, featuring Kabza De Small, DJ Maphorisa, and Mellow & Sleazy, edifies this. It speaks to long stretches of being outside-outside: partying it up with zest, no time to rest. To be young and full of raving joie de vivre! Monate Mpolaye – good times kill me – as another Amapiano song in Sepitori goes, affirms that epicurean excess in South Africa is alive and well. Young South African people are sustaining the country’s complicated drinking culture that is riddled with a particular socio-political context, specific to the country’s colonial and apartheid histories.

The linguistic register of ‘Straata’, beyond what it means, is intrinsically fugitive due to the nature of what a street represents. Indexically, the street signals mobility, transientness, pathways and, often, people on the move. Movement determines a street’s dynamism, adding to its functionality as a public space. However, the street’s general functions and connotations are also historical, social, cultural, and political too – especially in South African townships. Streets as public spaces for gathering played a significant role in the fight against apartheid, including being the venues for the protests that catalysed its end. These historical protests came with repertoires of cultural production that engaged symbiotically with the omnipresent possibilities for violent death or defiant survival.

South African social scientists Nomagugu Ngwenya, Nick Malherbe, and Mohamed Seedat argue that focusing on cultural production within protests can help to develop nuanced perspectives of how the political and the structural collide. They add that, by exploring which symbolic cultural repertoires protesters draw from, an exploration of the ‘performative processes’ of protests is possible. Such a shift in the matrix of cultural meaning within protest initiates an observation of how politics is shaped by a dynamism of the symbols at the disposal of the collective engaging in protest action. This creates a shift where the protester is a dynamic social actor, and thus a legitimate producer of both knowledge and culture. This is especially evident in the political and cultural repertoires of toyi-toyi, a music–dance compound of chanting, high-stepping, and jumping associated with anti-apartheid protests in South African townships, which persists into the post-apartheid era. In their research on this southern African performance protest symbol, Jocelyn Alexander and JoAnn McGregor, who interviewed former Robben Island prisoners and members of Umkhonto we Sizwe, write:

As Murphy Morobe put it … “… you can’t think of

ungovernability of the township politics without

the ‘toyi-toyi dance.’ For South African youth leaders,

the ‘toyi-toyi dance’ was ‘as African as big funerals’

and offered ‘an alternative to violent anarchy.’ Scholars

have credited its upbeat energy with creating ‘social

solidarity’ alongside the ‘militarisation of youth culture’.”

These are some of the Street dynamics the majority of the country’s Black youth are born into, the situated context implicitly or explicitly informing their orientation of being outside-outside. In his musician tag – Ase Trap tse ke Pina tsa ko Kasi (It is not Trap Music; it is music from the townships) – Focalistic, the pop culture youth arbiter, implies this knowledge.

In the opening shot of Focalistic’s 16 Days No Sleep music video, we are met with cascading aerial shots displaying a sprawling background of the Union Buildings, complete with manicured lawns and a towering nine-metre-high bronze statue of the iconic Nelson Mandela, the first president of democratic South Africa. His arms are sculpted permanently outstretched, with one foot stepping ahead, anticipating an embrace. In subsequent shots, we are led to make connections between the country’s political histories and the socioeconomic realities in post-apartheid South Africa: Sojourning snapshots of small-scale Black vendors at the side of a road selling fresh produce, including a sack of potatoes for R30. Soon afterwards, to our surprise, Focalistic, the president of the Streets, now joined by DJ Maphorisa (Madumane), is seen clad in an emerald-green reflective workwear uniform. They ride-surf a bin-collection truck making its rounds collecting refuse in leafy suburbia: the proletariat hard at work, diligently picking up the indulgences of the rich from the lawns of their excessive manors, complete with double-storey mansions and other proletariat staff, like servants. With the symbolic video introduction concluded in less than 30 seconds, the lyrics of the song start with Madumane’s recital. He is now characterised as the owner of the manor. He is dressed in a red Versace gown with a hefty monogram, Cuban links, designer sunglasses, a bucket hat, and socks and slides, chanting the reprise of the song in Sepitori. His bars are inferable, waxing and oscillating between the very real socioeconomic inequities that distinguish South Africa – lack and excess:

[Verse 1: Madumane]

’Sang tima metsi, worse summering (Do not deny me water, especially in summertime)

Ke di kuku, ke di kuku(They are cookies, they are cookies)

Re dasha ka gemere (We dash/mix with ginger beer)

Nama etswa ka meno (Meat comes out with teeth)

Le Porsche Panamera (The Porsche Panamera)

Soft ting, ke skhaftin (Soft thing, it is a lunch tin)

Le o ka ntima metsi (Even if you deny me water)

O e kreya e nwelwe (You will find that I have already drunk)

A ke reke six pack (I do not buy six pack)

Mara o kreya ke gymile (But you will find me in the gym/prepared)

Ma’ongenamali, phum’elinini (If you do not have money, get out of line)

Besi ghudla, ra khutsa (We were chilling, resting)

O kreya flighting (You will find me on a flight)

Madumane’s opaque lyrics skirt around the social life of Straata and its manifestations in nightlife and partying, typifying consumerist habits of class revealed in the names of luxury car brands, alcohol, leisurely spare time, and having flights to catch: the general benefits of social upward mobility. A mobility Madumane is certainly versed in: like Focalistic, he is a famed Amapiano superstar himself. Aptly, his nickname is revealing: in Sepitori, it is popularly used to refer to someone who is famous; more recently, he has been stylising it as “MaduMoney”. Within and beyond this song, both Madumane and Focalistic represent a precarious Black upper-middle class that has every reason to be outside-outside and grounded in the harsh realities of Straata, particularly in the Black South African township where fugitive possibilities contend with survival practice. Another South African musician and producer, Spoek Mathambo, who coined the term ‘Township Tech’ to describe his sound, spoke to music journalist Matthew Collin for his 2018 book, Rave On: Global Adventures in Electronic Music, saying:

A lot of electronic music [in South Africa] is party music, and for the last 20 years we’ve had a big reason to celebrate... Being a democracy for a first time, that creates a culture all on its own, people being free to move around where they used to not be able to... A lot of the music culture and party culture comes directly from the fact that it is a freedom party – not just any party, but a freedom party... It’s not just the freedom to express oneself but the literal thing of being able to go to different place at different times because there were curfews before that. Because of their race, people wouldn’t be allowed into certain establishments. It’s a very functional, real freedom, not just freedom of expression. Being able to be in the street, 2,000 of you with a sound system without the army shooting you down – that’s what it’s about.

Throughout the music video, Madumane and Focalistic cruise around in what is arguably the most desired status symbol in South African townships, the BMW 325i, colloquially known as Gusheshe. They take it for a spin in a township, a context which represents the origin of both of them, and which is the bedrock informing their backgrounds, socialisations, and music. In the street, kids are running after both the converted car and the superstars in it. Here, there is ambiguity as to whether Madumane and Focalistic cruising in the car are to be characterised as refuse-collecting labourers or as head-to-toe designer-clad rich and famous stars living in mansions and taking over South African youth culture one dancefloor party hit at a time.

This obfuscated ambiguity speaks to an unsettled Black middle-class identity that fugitively moves in and out of the township, the suburbs and, sometimes, overseas. These post-apartheid manifestations continue to be a preoccupation for the so-called ‘born-free generation’ – those born at the time of or after the country’s democratic transition. Articulations of this unsettledness are rife among a repertoire of, especially, Black musical practices, such as Hip-Hop and Kwaito (a musical repertoire, highly popular from the late 1980s to early 1990s, that was created by South Africa’s Black youth at the precipice of the country’s democratic transition). They have always been attuned to the embodied awareness of the socially upward mobilities of fame and fortune, as well as to the alienation these bring. “You can take me out of the ghetto, but you can’t take the ghetto out of me”, as the popular adage goes.

In my own Masters research in Fine Art, I look at the curatorial infrastructures of Straata, using Amapiano from Pretoria’s townships as case studies to argue that nightlife ecologies, often maintained by marginalised Black South African youth, become creative forms of Black being. In other words, the ecosystems of nightlife of young Black people should be valued. South African nightclubs and the country’s club culture, broadly, are huge engines for creativity. This is evidenced in the country’s current cultural export, dance music, specifically, Amapiano. These are spaces that are also ostensibly social and have political histories of collective organising. Shebeens (illicit bars in the townships during apartheid) were places where furtive anti-apartheid discussions could take place. Considering the history of beer-brewing in South Africa, they were also sites of fugitive negotiation relating to feminist discourse: shebeens were mostly run by Black women, known as shebeen queens. Black women who migrated to the cities, particularly during South Africa’s mining revolution, were often unemployed, and selling alcohol became a form of income generation and, subsequently, of economic freedom. Thus, as with obviously recognised cultural institutions such as museums, theatres, and art galleries, the country’s nightlife should be recognised as part of a lineage of studious creative industries. Germany’s most famous nightclub, Berghain, in Berlin, was officially designated a cultural institution in 2016, giving it the same tax status as the city’s opera houses and theatres. Meanwhile, the Swiss city, Zurich and Belgium’s capital city, Brussels, recognised their respective nightclub scenes as part of their ‘intangible cultural heritage’, with the former getting a co-sign from UNESCO.

When it is the turn of ‘President ya Straata’ to recite his verse, which includes an interpolated chorus of another song from Pretoria’s 2000s Bacardi House music era, we meet him in a clandestine parking lot. One of those cordoned off for superstars and presidents with tight security details. He is surrounded by an entourage that includes bodyguards, dancers, and make-up artists fawning over him. Dressed now in all black, nil flashy logos except for a Prada bucket hat. Focalistic’s lyrics generally refuse literal translation because they largely operate within a poetic register rather than as figurative signification, and sometimes they require an insider’s Pretoria/Sepitori knowledge base to discern their meanings. It is no different with this song: its interpolated chorus, too, is closer to incantation than to lyrics. Where his chorus messaging is discernible, he insists on the partying going on, as per the instructions in the song’s title – “16 Days No Sleep”:

[Chorus 2x: Focalistic]

Vele, vele, vele, vele

Vele, vele, vele, vele

Patje, patje, patje, patje

Patje, patje, patje, patje

Ma’sesubeleng

Bareng? Eh bare 16 Days No Sleep

O ke patje o mo wete

O ke leGogo le le sharp

Peter o rata bana ba ba wete

Banyana ba o tswa ka stack

As the music video enters its coda, we see Focalistic joined by another posse in another parking lot, though this one is more rundown, with a derelict stadium in the background. Him and his crew, all Black men, each chill on their own set of Gusheshe wheels, and the crew surround Focalistic in a semi-circle as he takes the centre, reciting the lyrics to his song. The day wanes and we are transported to an evening of another aesthetic and another creative practice of straata: diSpini – street car-racing with the Gusheshes spinning doughnuts. As the video concludes, it lulls us with in-and-out architectural drone shots of Pretoria’s city skyscrapers and then moves back to the township with delighted kids hailing the Gusheshe in the street during the day. Eventually, our eyes settle in a clinical white room with a day bed, designer luggage bags, and a bottle of Jägermeister plonked on a gold side table. Within seconds, Focalistic appears in the centre with a slow-motion pan, ‘drip checking’ his all-black designer outfit, complete with a stack of ‘Randelas’ (notes of South Africa’s currency, the rand, have Nelson Mandela’s portrait on one side). Here, the president of the streets flagrantly flaunts his wealth while making a statement – that, inasmuch as nightlife can be stratified by class, being outside-outside takes many social forms in South Africa. Or, as geographer Mahlatsi Malaika, opining on a trending conversation accusing Black South Africans of turning a farmer’s market into a place of partying, puts it: “Black people generally struggle with gathering in public spaces without turning these into groove” – explaining that this is because the township, with its particularities of straata, has “shaped the behaviours, experiences and thinking of their people” and driving home the point that the township is where socialisation happens for many Black South Africans. In Cape Town, early morning coffee raves have recently gained fanfare. Cappuccinos are guzzled to thumping electronic music as the caffeine energises you on the coffee shop’s pavement turned dancefloor and hopefully readies you for work. Even some 24-hour grocery shops in Cape Town are decked with CDJs ready to host second-location after parties.

––– –––

While young people in other parts of the world are going out less frequently, South African youth have democratised ways of being outside-outside. They are partying and turning general social events or rituals into cultural experiences synonymous with nightlife. The bana ba straata allegations are confirmed, complete with a self-appointed president. South African youth’s detachment from the broader global trend of some of the world’s young people going out less often is salient. It reveals how layered something as clichéd as partying is in South Africa. Socioculturally and politically, South Africa’s nightlife, outside-outside in the streets, is textured with histories of struggle. Thus, the subsequent residues of these histories, as they appear in post-apartheid South African youth’s cultural nightlife, are not a surprise. Focalistic’s leadership as the streets’ president is promising. As a committed amapiano superstar and cultural ambassador for its lifestyle, along with his dedication to youth gaiety – and a political science degree for some scholarly legitimacy – he might be an important key to preserving our nightlife ecologies.